Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong

Hermit Island and buried treasure: ‘The money consisted of gold, silver, English souvereigns and a few Mexican dollars’

One legend of the Apostle Islands is about a treasure buried by barrel maker William Wilson of Hermit Island in the mid-1800s. One story says the treasure was $90,000 in coins. Below is a passage from Benj. Armstrong’s 1892 book about his friendship with the recluse, the counting of some of Wilson’s money and finding the hermit dead in his island cabin with only $60 hidden behind a clock:

“In the year 1845 there came and settled upon this island a man by the name of Wilson — his first name I have forgotten. He lived there alone, neither family or neighbor and would not allow anyone to land, using his gun to enforce his orders when necessary. He wounded several people, but never killed anyone that I ever heard of ... He told me stories of his adventures and claimed that he embarked with the Hudson Bay Company when a boy and was transferred from place to place, even to the Rocky Mountains, but the route he took he could not or would not explain, but thought for many years he was a life prisoner with them as he could see no way to escape from the company. Finally he made his way to Lake Superior but by what route he was unable to say but said his sufferings and hardships before reaching the lake were terrible ... He was monarch of the island and all he surveyed. He had no pets except chickens and a rat and would allow no other animal about him. He kept liquor by the barrel though I never saw him under its influence and never knew him to offer a drink to anybody. He ordered one barrel of whisky through me. During some of these years I lived at Oak Island, probably two and a half miles from the hermit's house by the route we took with our boats. He sometimes came to my place for a visit but would never stay more than an hour at a time. For two or three years I bought what hay grew in a little meadow back of his house ... Through this dealing with him and his visits to my house there grew up an acquaintance which in him amounted to a friendship and he appeared to look upon me as the best friend he had. At the time the barrel of liquor came that I ordered for him he came to the landing at my place with his boat for it and after it was loaded into the boat he insisted on my going with him to help get it out of the boat, saying: ‘The men you have offered to send along I don't want,’ and continued: ‘I will pay you for the liquor over at my house and bring you back as soon as we have finished that business.’ I went along and assisted him in unloading the barrel and getting it ashore when he requested me to come into his house and he would pay me for the whiskey. He brought out either three or four bags of coin in buckskin and one stocking-leg filled with coin, and laid them on the table .... I put the money he had paid me in my pocket and proceeded to count his. I put each $100 in piles, there being about $1,300. The money consisted of gold, silver, English souvereigns and a few Mexican dollars ... During 1861 my folks told me they had seen no smoke from the old man's chimney for a few days ... A few days after this it was again reported that there was no smoke from the old hermit's chimney. The circumstance now led me to believe that something had befallen the old man, for he was not in the habit of going away from home ... I found Judge Bell and asked him if he had seen Wilson lately. He answered that he had not seen him in two months ... The judge got a boat and some men and we went to the old man's island together and found him dead upon the floor of his cabin and appearances indicated that he had been murdered. I then revealed to the judge what I had seen and done some years before at his request and thought that money must be hidden somewhere about the house. The judge and his men instituted a search for the treasure but only found about sixty dollars which was in a box behind the clock and was entirely hidden from sight when the clock was in place ... Nothing more is known by the people of Lake Superior of this strange man or from whence he came except what he told himself.”

The 1960 book “La Pointe: Village Outpost on Madeline Island” by Hamilton Nelson Ross adds: Wilson “was buried in an unmarked grave, at own request, in the mission cemetery on Madeline Island ... For some years thereafter, rumors of Spanish doubloons and pieces of eight took treasure seekers to his Hermit Island home, but, so far as is known, no one found any of the trove.”

Web resources on the Apostle Islands region

National Park Service’s Apostle Islands National Lakeshore page

Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

Bayfield.org — Chamber of Commerce and Visitor Bureau

Madelineisland.com — visitor information

Wisconsin Historical Society page on Hermit Island’s namesake and Armstrong

Big Bay State Park on Madeline Island

Friends of the Apostle Islands

Native American Tourism of Wisconsin

Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission

Armstrong was a framer of the region’s economy

The “Visitor’s Guide to the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore” by Dave Strzok notes: “In the mid-1800s, Benjamin Armstrong and his wife lived near the southeast sand point on the island. Armstrong had been an Indian agent and was one of the framers of the economy in the Chequamegon area. He was reputed to have been rewarded by grateful Chippewa who led him blindfolded, about three days southeast of Ashland to a place where he found and picked up gold nuggets lying on the surface of the ground. He apparently wished to return to the place but was subsequently blinded by an explosion of gunpowder that was thrown into his campfire while he was (traveling) along a trail between Ashland and Duluth. Though he regained much of his eyesight several years later, he could no longer recognize the place where the gold nuggets laid on the surface of the ground. It was Armstrong who discovered the deceased Hermit Wilson on Hermit Island in the 1850s.”

Armstrong as an entrepreneur on Madeline Island

Benjamin Armstrong owned a store, home and land on the largest of the Apostle Islands. A contemporary of his was Julius Austrian who owned 4,000 acres on Madeline Island. “Austrian’s attempts at eminence attracted competitors. Chief among them was Benjamin Armstrong, an Alabama native who was married to an Indian woman and who immersed himself in Chippewa and northern Wisconsin lore. He owned about 1,100 acres on the island, of which 130 were cultivated,” according the book “Madeline Island & the Chequamegon Region” by John O. Holzhueter. Armstrong has been called “one of the most intriguing characters in the history of the Apostle Island.” Click here for more The book “A Northern Land: Life with the Ojibwe” says Armstrong was “the chronicler of Ojibwe history in the Apostle Island region.” Click here for more

Armstrong’s commercial logging and farming on Oak Island in Lake Superior

“Benjamin Armstrong is the best known of the traders who were working in the Chequamegon region in the 1850s,” according to the National Park Service book titled “People and Places: A Human History of the Apostle Islands.” The book also notes: “Born in Alabama in 1820, Armstrong came to the St. Croix River Valley in 1840. Sometime in the early 1850s Armstrong established a store at La Pointe. In 1855 he moved with his wife and four children to the southwestern shore of Oak Island, where they built a house, barn, and dock and cleared 40 acres, five of which they cultivated. At his Oak Island home and trading post, Armstrong sold hardwood fuel to steamboats and traded with the Ojibwe. In 1861, when the government appointed Armstrong to be interpreter to Indian agent Webb, he moved with his family to Bayfield. Armstrong later moved to Ashland where he held several government offices and where he died in 1900.” The book adds: “Oak Island, the highest of the Apostle Islands, especially lent itself to logging, with steep terrain and many ravines that aided in moving the logs to shore. The first commercial logging intended for a market beyond local building needs began on Oak Island in the late 1850s, when Benjamin Armstrong began cutting hardwood for steamboat fuel.” Armstrong was among the first to engage farming activity on an Apostle island other than Madeline Island when he farmed the five acres on Oak Island beginning in 1855. A Bayfield newspaper in 1860 reported: “We have been presented with the tallest specimen of rye yet brought to Bayfield. It measures seven feet six inches, and was raised by (Armstrong) at Oak Island. He also brought in a splendid lot of the King Phillip corn.” Click here to read more from “People and Places: A Human History of the Apostle Islands” by Jane C. Busch.

National Park Service brochure on Oak Island

The brochure notes: “In the 1850s, Benjamin Armstrong from Alabama built a cabin on the island and lived there for about six years. He learned the Ojibwe language and served as translator and advisor to tribal elders, accompanying them to Washington to meet with Presidents Fillmore and Lincoln.” Click here to view a copy of the Oak Island brochure.

More on Oak Island. Click here to read more about the Armstrong Family and their years on Oak Island

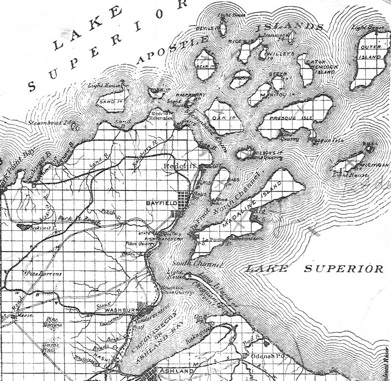

Lake Superior’s Apostle Islands and Chequamegon Bay

Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong helped chart the history and future of the Apostle Islands and the Chequamegon Bay territories of Wisconsin. Madeline Island is the spiritual center of the Chippewa religion and Buffalo’s birth and burial resting place. The 1854 Treaty at La Pointe was signed at the island’s village. Madeline Island is where Buffalo and Armstrong left by canoe on their 1852 journey to the nation’s capital to halt the removal of the Lake Superior Chippewa to lands to the west. Armstrong had a home and store in La Pointe and is considered “the best known of the traders who were working in the Chequamegon region in the 1850s” and “one of the most intriguing characters in the history of the Apostle Island.” Below read about Buffalo’s last days on Madeline Island. And read about Armstrong’s connection to other islands in the chain, including his family homestead on Oak Island and his friendship with the recluse of Hermit Island.

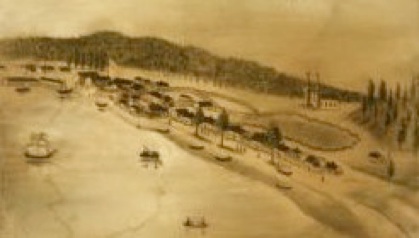

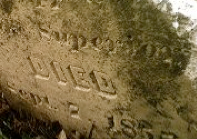

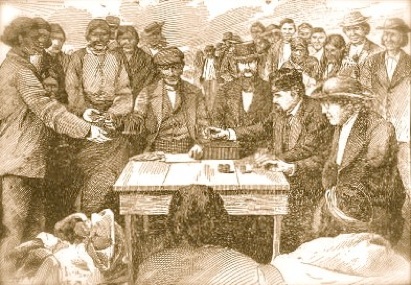

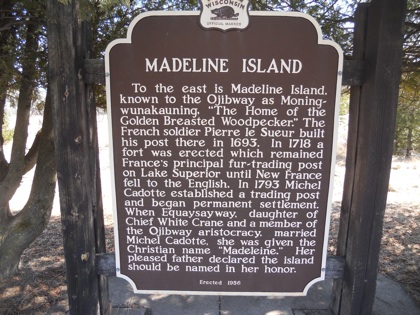

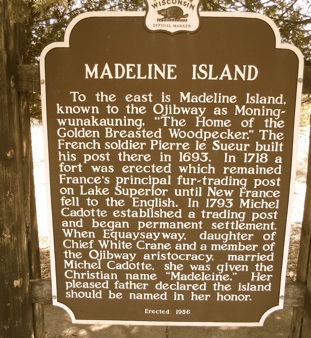

Images from Madeline Island and the Lake Superior shore: An illustration from Benjamin Armstrong’s book of a treaty payment at La Pointe; Chief Buffalo’s gravestone; construction of the Red Cliff Band’s Legendary Waters Casino; state history marker about Madeline Island; and a modern-day winter view of Madeline Island from the shore near the Red Cliff Reservation.

How do you say Chequamegon?

Wisconsin Historian John O. Holzhueter writes: “As for pronunciation, Chequamegon is a twister. For a time, Wisconsin’s radio network used it as an informal test for apprentice announcers. If a novice could slide his tongue around Chequamegon, he could not be stumped. Even so, a choice exists. Some authorities cite 19th century writers who insist it is she-kwah-me-gun; others cite local pronunciation, in which the initial consonant of the second syllable is dropped, and the word becomes she-wah-me-gun.” He notes that the region’s name derives from Chippewa word shagwaumikong, meaning soft beaver dam.

Buffalo’s last days on the island

Benjamin Armstrong on Chief Buffalo’s final days and his burial:

“I will now go back to 1855. About the middle of September word was sent to me at Oak Island by Agent Gilbert that the annuities had arrived for the first payment under the treaty of '54, and if I was able to attend he should be pleased to have me do so; that he had some talking to do with the Indians and that they as well as himself would like to have me present to hear it. I arranged matters to leave Oak Island and as I owned a house at La Pointe moved my family there for the fall, that I might have their care. Chief Buffalo had been prescribing for and treating my eyes and as he was then sick at La Pointe I had parties take me to his home. I had not talked with him more than an hour when it became apparent that he was quite feeble. I bought him articles of food and did all I could for his comfort that night and the next morning visited the agent and commissioners and told them of the old chiefs illness and said I did not think he would be able to attend the councils that fall. Col. Manypenny and myself visited the old man that day. The Colonel gave him his best wishes and told him that anything he wished to eat should be brought to him and hoped in a day or two he would be able to come down and hear what the agent had to say. But the old man was never able to attend the councils (again) ... Chief Buffalo not being able to meet the commissioners, I requested them to go with me to see him, stating that I did not think he would last more than two or three days and I should like to have them talk with him on business matters, as he had told me himself that he could live but a few days at most ... After some further talk the commissioners left, but I remained with the old veteran until he died. I gave him a decent burial. Calling all parties together we formed a procession and marched to the Catholic cemetery at La Pointe where we laid the old chief to rest. I ordered and placed in position a tombstone at the head of his grave ...”

The 1885 book “Kitchi-Gami: Life Among the Lake Superior Ojibway” by Johann Georg Kohl says this regarding the chiefs from Madeline Island: “La Pointe belongs to a larger group of islands, which the French missionaries named Les Isle des Apotres. They play a great part in the Indian traditions, and seem to have been from the earliest period the residence of hunting and fishing tribes, probably through geographical position and the good fishing in the vicinity. The fables of the Indian Creator, Menaboju, often allude to these islands, and the chiefs who reside here have always laid claim, even to the present day, to the rank of princes of the Ojibbeways.”

The Madeline Island folk song “Over At Old La Pointe” contains this verse: “The Chippewas know its holy ground, spirits are in the air/

On his journey to the other world, Chief Buffalo left from there.”

This site is published by a member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. Click here for more information