Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong

‘The world showed up dark before me’

Excerpt from Benjamin G. Armstrong’s memoirs:

“Now I must take you to Oak Island, which was my home from the spring of 1855 to the spring of 1862. I was confined to my house during all of this time except such time as I was seeking or receiving medical aid. Being blind and financially embarrassed, the world showed up dark before me. I had exhausted all my ready money in conducting the late treaty and had nothing to fall back upon except a few tracts of land I had secured and the furs I had accumulated the previous winter. I had my furs baled up and they turned out as follows: One of martin skins, one of beaver and otter skins. These I consigned to parties in Cleveland, Ohio, in care of Cash and Spaulding, Ontonagon. They should have brought me $1,200 but I never realized one dollar for them. I inquired of Cash and Spaulding concerning the furs and was told that the parties in Cleveland would not receipt for them or receive them until some skins that were missing from the bales should be accounted for, claiming they had been broken open in transit on the boat.”

Armstrong Family homesite and Oak Island’s cultural resources

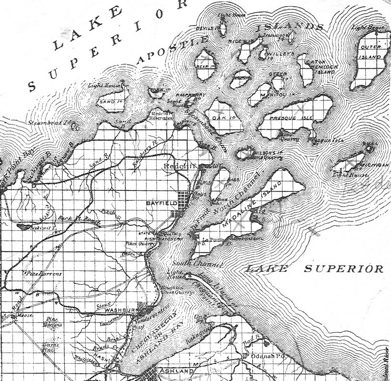

From the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Master Plan on cultural resources of the island notes about site of of Armstrong’s cabin, clearing and garden: “The reported American Fur Company buildings on Ironwood Island and the site of the cabin of Benjamin Armstrong, an early trader and representative of the Chippewa in treaty negotiations, are instances of such potential resources.” Click here to read the master plan.

The Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Wilderness Study/Environmental Impact Statement (2004) notes: Oak Island’s “historical highlights include archaeological sites, a Native American sugar bush, a circa 1850 steamboat wood yard and dock (probably the first such wood yard in the region), the mid-19th century homestead of the Benjamin Armstrong family (significant figures in the area and especially Anishinabeg history) ...” Click here to read the study.

Web resources on the Apostle Islands region

National Park Service’s Apostle Islands National Lakeshore page

Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

Red Cliff Band of Lke Superior Chippewa

Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

Bayfield.org — Chamber of Commerce and Visitor Bureau

Madelineisland.com — visitor information

Wisconsin Historical Society page on Hermit Island’s namesake and Armstrong

Big Bay State Park on Madeline Island

Friends of the Apostle Islands

Native American Tourism of Wisconsin

Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission

Armstrong Family and Oak Island

More than 160 years ago, Benjamin G. Armstrong, his Ojibwe wife and their children arrived on Oak Island in Lake Superior to start a new life. They built a home and dock and established a trading post on the island. They cleared land, farmed it and sold wood to steamers traveling Lake Superior in the years before coal became the fuel of choice.

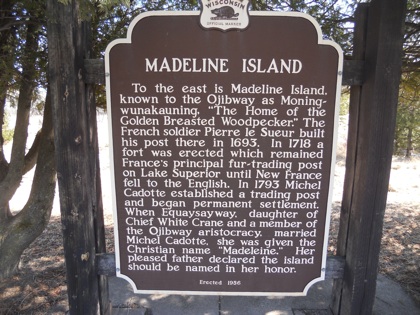

These were history-making acts, away from the village of La Pointe and Madeline Island where Armstrong earlier had made a name for himself as a trader, farmer, guide and Indian interpreter.

The National Park Service brochure on Oak Island notes: “In the 1850s, Benjamin Armstrong from Alabama built a cabin on the island and lived there for about six years. He learned the Ojibwe language and served as translator and advisor to tribal elders, accompanying them to Washington to meet with Presidents Fillmore and Lincoln.” Click here to view a copy of the Oak Island brochure.

According to the National Park Service publication titled “People and Places: A Human History of the Apostle Islands,” Benjamin “Armstrong was among the first to engage farming activity on an Apostle island other than Madeline Island when he farmed the five acres on Oak Island beginning in 1855.” Click here to read more from this publication. A Bayfield newspaper in 1860 reported: “We have been presented with the tallest specimen of rye yet brought to Bayfield. It measures seven feet six inches, and was raised by (Armstrong) at Oak Island. He also brought in a splendid lot of the King Phillip corn.”

The Park Service publication further notes: “Logging for a broader market began on Oak Island during the 1850s, when Benjamin Armstrong began cutting hardwood for steamboat fuel.”

This publication says, “Benjamin Armstrong is the best known of the traders who were working in the Chequamegon region in the 1850s.” The “Visitor’s Guide to the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore” by Dave Strzok notes: “Armstrong had been an Indian agent and was one of the framers of the economy in the Chequamegon area.”

This paints a picture of success, but the Armstrong family’s years on Oak Island also were ones of hardship. During this time, the Panic of 1857 hit and is considered first worldwide economic crisis. Another reason for the family’s hardship was that Benjamin Armstrong had been temporarily blinded, seeking remedies during his years on Oak Island ranging from Chief Buffalo “prescribing” and “treating” his eyes to taking a trip on the Iron City streamer in an unsuccessful attempt to seek medical treatment in Ohio.

Also, “Armstrong had gotten deeply in debt ... for goods which he had furnished to the Indians,” according to the book “Duluth and St. Louis County, Minnesota: Their Story and People, Volume 1” (1921). Click here to read this book. Armstrong confirms this in his memoirs: “Being blind and financially embarrassed, the world showed up dark before me. I had exhausted all my ready money in conducting the late treaty and had nothing to fall back upon except a few tracts of land I had secured and the furs I had accumulated the previous winter.” He also notes that “at the time I scarcely knew from whence my next sack of flour would come.”

The Oak Island years also figure into historical claims into the title of a square-mile section of present-day Duluth that Armstrong say he received through the Treaty at La Pointe with the Chippewa in 1854. Two men who eventually claimed title to this land traveled to Oak Island while Armstrong was blind to make deals over the property. Armstrong said neither ever completely paid him for rights to the land. Others say Armstrong was not swindled out of the money and didn’t even have the right to sell the land in the first place. Click here here to learn more on that view. The land in Duluth, known as the Buffalo Tract, later was at the center of two U.S. Supreme Court cases.

The Oak Island years

Spring 1855 — Armstrong and his family moved to the southwestern shore of Oak Island. There they built a house, barn and dock and cleared 40 acres. They farmed five acres.

Fall 1855 — Armstrong temporarily moved back to his house on La Pointe, Madeline Island. He states in his memoirs: “Word was sent me at Oak Island for Agent Gilbert that the annuities had arrived for the first payment under the treaty of ’54 and if I was able to attend he should be pleased to have me do so; that he had some talking to do with the Indians and that they as well as himself would like to have me present to hear it. I arranged matters to leave Oak Island and as I owned a house at La Pointe moved my family there for the fall that I might have their care. Chief Buffalo had been prescribing for and treating my eyes and as he was then sick at La Pointe I had parties take me to his home. I had not talked with him more than an hour when it became apparent that he was quite feeble. I bought him articles of food and did all I could for his comfort that night and the next morning visited the agent and commissioners and told them of the old chief’s illness and said I did not think he would be able to attend the councils that fall. Col. Manypenny and myself visited the old man that day. The Colonel gave him his best wishes and told him that anything he wished to eat should be brought to him and hoped in a day or two he would be able to come down and hear what the agent had to say. But the old man was never able to attend the councils more.” Chief Buffalo during this time.

July 1856 — Armstrong writes in his memoirs: “About the first of July 1856, Mr. Spaulding of our company, came to my home on Oak Island and told me that my claims against the Indians for old back debts that were arranged for in the treat of 1854 had been allowed by the government and amounted to just $900, and that as he was going to Washington in a few days and coming right back and if I would give him an order for the money, and thinking this the quickest way to obtain it, I agreed. He wrote out an order himself and I signed it, but being blind, I cannot say whether I signed my name or made my mark. Mr. Spaulding went away, and as far as I am concerned, the money went with him.”

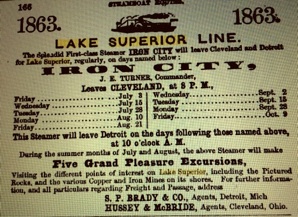

Fall 1856 — Frederick Prentice arrives on Oak Island to discuss purchasing part of the land in Duluth that Armstrong received through the 1854 Treaty with the Chippewa. The complete payments never arrived, but Armstrong does say some “goods and oxen” were “received at Oak Island by the steamer Iron City.” Daniel S. Cash later travels to Oak Island where Cash offers a loan secured by part of the land in Duluth. Armstrong says he again didn’t receive proper payment.

1856-1857 — General Land Office survey notes describe Armstrong’s house, dock and clearing.

1857 — Panic of 1857 hits the U.S. economy.

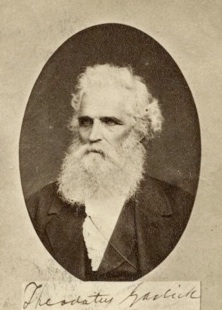

1857 — Armstrong travels on the Captain Turner’s Iron City steamboat to Cleveland to seek medical firm of Garlick & Ackley in hopes of restoring his eyesight. The doctors say they cannot help him.

Late 1850s — “Oak Island, the highest of the Apostle Islands, especially lent itself to logging, with steep terrain and many ravines that aided in moving the logs to shore. The first commercial logging intended for a market beyond local building needs began on Oak Island in the late 1850s, when Benjamin Armstrong began cutting hardwood for steamboat fuel,” notes a National Park Service publication.

1859 — Daniel S. Cash sues Armstrong in Duluth for $10,000 saying he never received the deed for the land in the Buffalo Tract in Duluth. Armstrong never directly mentions this case in his memoirs. But he does at one point state discussing Cash: “I tried to employ council many times to take hold of the matter, but not having money to advance for such services, I failed to obtain any help in that direction.”

1860 — A Bayfield newspaper reports: “We have been presented with the tallest specimen of rye yet brought to Bayfield. It measures seven feet six inches, and was raised by (Armstrong) at Oak Island. He also brought in a splendid lot of the King Phillip corn.”

Late 1860/Early 1861 — Armstrong’s eyesight returns.

Early 1860s - “Federal government appointed Armstrong to be interpreter to local Indian agent and Armstrong moved with his family to Bayfield. Armstrong later moved to Ashland where he held several government offices and where he died in 1900.”

Note: Oak Island in Chippewa is Mitigaminikang Miniss.

This site is published by a member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. Click here for more information

Armstrong’s memoirs mention the Iron City steamboat during his years on Oak Island.

Theodatus Garlick, one of the doctors in Cleveland who Armstrong consulted in 1857 to help restore his eyesight. He traveled from Oak Island to Ohio on the Iron City steamer.