Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong

U.S. Supreme Court cases

The U.S. Supreme Court in the late 1800s heard two property law cases regarding the land granted to Benjamin Armstrong via the federal government’s 1854 Treaty.

Prentice v. Stearns (1885): The actions of Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong and his wife Charlotte Armstrong were central to the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1885 case of Prentice v. Stearns, although they weren’t parties in the lawsuit. In dispute was what the Armstrongs sold to Fredrick Prentice of Ohio. Prentice was suing another person who was in possession of the land and claimed the title. Prentice argued that the exact description of the land he bought didn’t matter because he wasn’t buying a defined parcel of land from the Armstrongs. Rather, he argued that the Armstrongs were selling an interest in whatever they were entitled to under Buffalo’s grant in the Treaty of 1854. The court ruled: “The land described in the deed from Armstrong and wife to the plaintiff of September 11, 1856, is not the same land, in whole or in part, as that described in the patent from the United States to Armstrong.” Click here to read the entire court decision

Here’s how a July 4, 1884 story in the New York Times headlined “The Ownership of Duluth” described the complicated legal argument of those being sued by Prentice: “The defendants claim that it was before Armstrong got his title that he made a quit-claim deed to Frederick Prentice, the plaintiff in the suits, and it is under this deed that Prentice puts in his claim. Armstrong, subsequent to the time of getting the patent, conveyed the lands to other parties, under which conveyance the present occupants hold. The defendants set up, first that the deed from Armstrong to Prentice does not include any of the land now in controversy. They also claim that at the time when Armstrong made the deed to Prentice he had no title to the land which he deeded. They claim further a number of points, among which is that deed was not duly recorded, so as to give notice to the world of its existence; that the deed to Prentice was made before any patients of the land were issued to anybody, (that is, in 1856) and the patents were not issued for these lands until 1858.” The article notes that if this other similar cars are decided for Prentice they “will be followed by a multitude of others against property owners in Duluth.”

Prentice v. Northern Pacific Railroad Company (1894): Fredrick Prentice didn’t give up after his court loss in 1885. He continued to file numerous claims to the land that now is Duluth. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1894 case of Prentice vs. Northern Pacific Railroad was one of those legal filings. In this lawsuit, he used another legal argument to try to secure an interest in the land. He lost again. The justices in this case again reviewed the 1854 treaty and Chief Buffalo’s grant to Benjamin Armstrong in detail. Click here to read the entire court decision

Other court cases also have cited Benjamin Armstrong. Perhaps most notable of them is the 1982 federal case of Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians v. Voigt. See this site’s “Armstrong Memoirs” page for more information on this ruling on off-reservation hunting and fishing rights.

Web resources

The Zenith City History site has an article titled, “The Saga of the Prentice Claim — aka the Buffalo Tract.” It notes: “The treaty with the Indians in which Chief Buffalo figured was made in September, 1854, and very shortly after its ratification the chief decided where he would locate his claim and did so. It is more than possible that in making his choice he had the advantage of the advice of some of the original Duluth boomers, who were speculating on his necessities and were not indisposed to take some advantage of them. Be that as it may, however, in two years after the treaty the Chief Buffalo tract, as it has ever since been called, had passed out of the chief’s hands and was securely vested in that of Benjamin G. Armstrong and wife.” Click here

The Perfect Duluth Day site has an article titled, “Chief Buffalo, Point of Rocks and The Mayor of Duluth.” Click here

For an alternative view of Benjamin Armstrong’s memoirs and the man himself, see “An Ethnographic Study of Indigenous Contributions to the City of Duluth.” It sets out to attempt to make a critical argument about Armstrong’s role in the loss of tribal land in what is now central Duluth. Click here here to learn more.

The book “Duluth and St. Louis County, Minnesota: Their Story and People, Volume 1” (1921) discusses Benjamin Armstrong, “a trader at La Pointe, who was married to a daughter of Chief Buffalo. Armstrong had gotten deeply in debt to (his supply company) for goods he had furnished to the Indians.” Click here to read this book.

Treaty with the Chippewa 1854

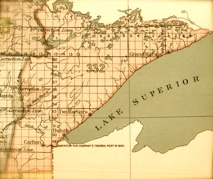

The U.S. government’s Treaty with the Chippewa in 1854 stopped the removal of the Lake Superior Chippewa from their homeland by eventually establishing reservations in Wisconsin, Minnesota and Michigan. The tribe in the treaty ceded much of the land in the Arrowhead region of Minnesota, although they retained hunting, fishing and other natural resource rights. Chief Buffalo was the first signer of the treaty. Article 2 specifically grants him the right to convey land. It states: “And being desirous to provide for some of his connections who have rendered his people important services, it is agreed that the chief Buffalo may select one section of land, at such place in the ceded territory as he may see fit, which shall be reserved for that purpose, and conveyed by the United States to such person or persons as he may direct.” Click here to read the entire treaty. For Wikipedia’s entry on the Treaty at La Pointe, click here. For a primer on treaty rights from the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission, click here.

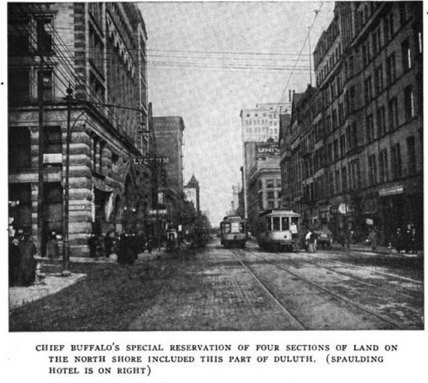

The Buffalo Tract — Duluth, Minnesota

The 1854 Treaty at La Pointe resulted in Benjamin Armstrong and his Chippewa wife Charlotte being granted a right to a large portion of the land that now is the Lake Superior port city of Duluth. How the Armstrongs lost the land isn’t a straightforward matter. Instead, it involves conflicting stories about sales of interest in parts of the land, payments that never came, disputes over agreements and boundaries, and U.S. Supreme Court cases.

Here is how Armstrong describes how he first obtained the right to the land, on page 38 and 39 of this memoirs:

“It was about in the midst of the councils leading up to the treaty of 1854 that Buffalo stated to his chiefs that I had rendered them services in the past that should be rewarded by something more substantial than their thanks and good wishes, and that at different times the Indians had agreed to reward me from their annuity money but I had always refused such offers as it would be taking from their necessities and as they had no annuity money for the two years prior to 1852 they could not well afford to pay me in this way. ‘And now,’ continued Buffalo, ‘I have a proposition to make to you. As he has provided us and our children with homes by getting these reservations set off for us, and as we are about to part with all of the lands we possess, I have it in my power, with your consent, to provide him with a future home by giving him a piece of ground which we are about to part with. He has agreed to accept this as it will take nothing from us and makes no difference with the great father whether we reserve a small tract of our territory or not, and if you agree I will proceed with him to the head of the lake and there select the piece of ground I desire him to have, that it may appear on paper when the treaty has been completed.’ The chiefs were unanimous in their acceptance of the proposition and told Buffalo to select a large piece that his children might also have a home in future as has been provided for ours. This council lasted all night and just at break of day the old chief and myself, with four braves to row the boat, set out for the head of Lake Superior and did not stop anywhere only long enough to make and drink some tea, until we reached the head of St. Louis Bay ... Here Buffalo turned to me saying, ‘Are you satisfied with this location? I want to reserve the shore of this bay from the mouth of the St. Louis river. How far that way do you want it to go?’ pointing southeast, or along the south shore of the lake. I told him we had better not try to make it too large for if we did the great father’s officers at Washington might throw it out of the treaty.”

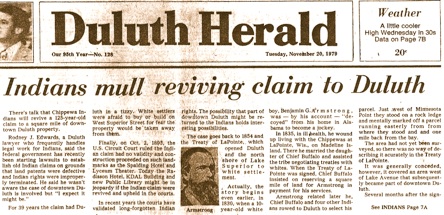

An article in the Duluth Herald on Nov. 20, 1979 reports: “The story begins even earlier, in 1830, when a 10-year-old white boy, Benjamin G. Armstrong was — by his own account — ‘decoyed’ from his home in Alabama to become a jockey. In 1835, in ill health, he wound up living with the Chippewa at La Pointe, Wis., on Madeline Island. There he married the daughter of Chief Buffalo and assisted the tribe negotiating treaties with whites. When the Treaty of La Pointe was signed, Chief Buffalo insisted on reserving a square mile of land for Armstrong in payment for his services. Armstrong related later he, Chief Buffalo and four other Indians rowed to Duluth to select his parcel. Just west of Minnesota Point they stood on a rock ledge and mentally marked off a parcel running easterly from where they stood and one mile back from the bay. The area had not yet been surveyed, so there was no way of describing it accurately in the Treaty at La Pointe. It was generally conceded, however, it covered an area west of Lake Avenue that subsequently became part of downtown Duluth.”

Please note that the Buffalo Tract is different from the Buffalo Estate, which was land in Wisconsin granted to Chief Buffalo on the shores of Lake Superior in Wisconsin. The “estate” land is now part of the Red Cliff Reservation.

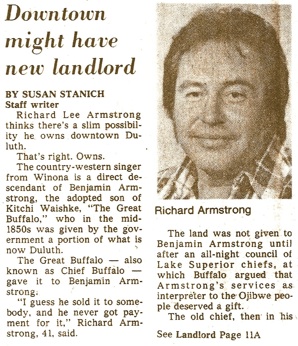

The song “Landlord of Duluth” by the late Ojibwe music man Richard Lee Armstrong tells the story of the land claims.

The song is available on iTunes on Richard Lee Armstrong’s Thunder of the Circle CD and on his Pretty Dream Woman CD.

Duluth Herald, Nov. 20, 1979

Duluth News-Tribune & Herald, Sept. 19, 1984

This site is published by a member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. Click here for more information