Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong

Sandy Lake Tragedy — or the Chippewa Trail of Tears

Many history books continue to overlook the death and suffering of the Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850. President Taylor’s administration and territorial officials wanted to move the Lake Superior Chippewa to lands to the west. Part of the scheme involved switching the annual treaty payments from Madeline Island in Wisconsin — spiritual gathering center of the Chippewa — to Sandy Lake in Minnesota. The trip required traveling by canoe and on foot for hundreds of miles. There were no supplies on hand when the Chippewa arrived in October. Agents finally made partial payments in December, but by then snow covered the ground and canoe routes were frozen. The officials responsible for the scheme hoped that worn-out tribal members wouldn’t make the trip home and would stay permanently. At Sandy Lake and on the trek home, more than 400 people died because of delayed and meager payments, tainted food, disease, inadequate housing and the cold weather. This and other events led to the 1852 journey to Washington by Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong to meet with President Fillmore. That trip resulted in stopping the removal of the Lake Superior Chippewa, returning the annuity payments to Madeline Island and eventually establishing reservations.

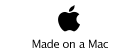

The treaty payments return to Madeline Island. From Benjamin Armstrong’s book, here’s an illustration with the caption, “Annuity payment at La Pointe.”

‘They had lost 150 warriors on this one trip alone by being fed on unwholesome provisions, and they reasoned among themselves: Is this what our great father intended?’

Passage from “Early Life Among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong” on unrest over the annuity payments and the start of the trip to Washington.

“They now all realized that they had been induced to sign treaties that they did not understand, and had been imposed upon. They saw that when the annuities were brought and they were asked to touch the pen, they had only received what the agent had seen fit to give them, and certainly not what was their due. They had lost 150 warriors on this one trip alone by being fed on unwholesome provisions, and they reasoned among themselves: Is this what our great father intended? If so we may as well go to our old home and there be slaughtered where we can be buried by the side of our relatives and friends. These talks were kept up after they had returned to La Pointe. I attended many of them, and being familiar with the language, I saw that great trouble was brewing and if something was not quickly done trouble of a serious nature would soon follow. At last I told them if they would stop where they were I would take a party of chiefs, or others, as they might elect, numbering five or six, and go to Washington, where they could meet the great father and tell their troubles to his face. Chief Buffalo and other leading chieftains of the country at once agreed to the plan, and early in the spring a party of six men were selected, and April 5th, 1852, was appointed as the day to start. Chiefs Buffalo and O-sho-ga, with four braves and myself, made up the party. On the day of starting, and before noon, there were gathered at the beach at old La Pointe, Indians by the score to witness the departure. We left in a new birch bark canoe which was made for the occasion and called a four fathom boat, twenty four feet long with six paddles.”

President Fillmore told the delegation ‘he would countermand the removal order and that the annuity payments would be made at La Pointe as before’

Passage from “Early Life Among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong” on President Fillmore stopping the forced removal of the Lake Superior Chippewa and ordering the treaty payments to be made at La Pointe:

“When O-sho-ga had finished his speech I presented the petition I had brought and quickly discovered that the President did recognize some names upon it, which gave me new courage. When the reading and examination of it had been concluded the meeting was adjourned, the President directing the Indian Commissioner to say to the landlord at the hotel that our hotel bills would be paid by the government . He also directed that we were to have the freedom of the city for a week. The second day following this (Congressman) Briggs informed me that the President desired another interview that day, in accordance with which request we went to the White House soon after dinner and meeting the President, he told the delegation in a brief speech that he would countermand the removal order and that the annuity payments would be made at La Pointe as before and hoped that in the future there would be no further cause for complaint. At this he handed to Buffalo a written instrument which he said would explain to his people when interpreted the promises he had made as to the removal order and payment of annuities at La Pointe and hoped when he had returned home he would call his chiefs together and have all the statements therein contained explained fully to them as the words of their great father at Washington.”

Note: O-sho-ga also is referred to as O-Sha-ga in other passages.

‘Tell him I blame him for the children we have lost’

Minnesota erected a State History Marker titled “The Ojibwe’s Sandy Lake Journey” in 2001 at Sandy Lake. Here’s part of what it says:

The text reads: “Tell him I blame him for the children we have lost” – Aish-ke-bo-go-ko-zhe (Flat Mouth), December 3, 1850.

“In late 1850, some 400 Ojibwe Indians perished because of the government’s attempt to relocate them from their homes in Wisconsin and Upper Michigan to Minnesota west of the Mississippi River. The tragedy unfolded at Sandy Lake where thousands of Ojibwes suffered from illness, hunger and exposure. It continued as the Lake Superior Ojibwe made a difficult journey home. In the 1840s, Minnesota politicians began pressuring the U.S. government to remove Ojibwe people from lands the government claimed they had ceded, or given up, in 1837 and 1842 treaties. Territorial governor Alexander Ramsey and others claimed they were acting to ‘ensure the security and tranquility of white settlements.’ But their true motivation was economic. If Indians were moved from Wisconsin and Upper Michigan onto unceded lands in Minnesota, local traders could supply the annuity goods the Government had promised to provide to the Ojibwe under the treaties, and they could trade with the Ojibwe themselves. Minnesotans could also build Indian agencies and schools in return for government funding and jobs. From the outset, the Lake Superior Ojibwe vigorously opposed removal. They pointed to the promises made at the treaty negotiations that they could remain on ceded lands. Knowing that the Ojibwe would not consent to removal, government officials devised a plan to entice the Ojibwe to Sandy Lake, hoping that they would simply remain here and abandon their homelands in Wisconsin and Michigan. In 1850, the Ojibwe were told to arrive at Sandy Lake no later than October 25th where their treaty annuities-cash, food and other goods promised in exchange for the land cessions-would be waiting for them. In prior years, these annuities for the Lake Superior Ojibwe had been distributed at La Pointe on Madeline Island in Lake Suprior, a traditional hub of Ojibwe culture and a more accessible location. By November 10th, some 4,000 Ojibwe had arrived. They were ill prepared for what they faced at Sandy Lake. The promised annuities were not waiting for them, and the last of the limited provisions that were available were not distributed until December 2nd after harsh winter conditions had set in. While they waited the nearly six weeks, they lacked adequate food and shelter. Over 150 died from dysentery caused by spoiled government provisions and from measles. Demonstrating their steadfast desire to remain in their homelands, the Ojibwe began an arduous winter’s journey home on December 3rd. As many as 250 others died along the way. On the same day, Aish-ke-bo-go-ko-zhe, the Ojibwe leader also known as Flat Mouth, sent word to Ramsey that he held him personally at fault for the broken promises that resulted in suffering and death. As word of the Sandy Lake disaster spread, so did opposition to the government’s removal policy ... Ojibwe leaders traveled to Washington to secure guarantees that annuities would be distributed at La Pointe and that the Ojibwe could remain in their homelands ...”

Remembering those culpable in the Chippewa Trail of Tears

The scheme in the late 1840s and early 1850s to move to Lake Superior Chippewa from their homes to Minnesota has been called the Ewing-Brown-Ramsey-Watrous plan. Those four individuals are Interior Secretary Thomas Ewing, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Orlando Brown, Minnesota Territorial Gov. Alexander Ramsey and Indian subagent John Watrous, all connected to the administration of President Zachary Taylor. Taylor’s removal order in 1850 failed when the bands ignored it. Ramsey and Watrous next devised the plan to move the annual payments from Madeline Island in Wisconsin to Sandy Lake in Minnesota. An apparent public outcry over the deaths and suffering at Sandy Lake in 1850 prompted the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington in 1851 to suspend the removal order, at least temporarily. But this didn’t stop Ramsey and Watrous from continuing their plans. Here’s a look at some of the officials culpable in the tragedy.

John Watrous

Indian Subagent John Watrous was the point person in the plan to move the Lake Superior Chippewa in the 1850s. Some records identify him as Major John Watrous. He urged the Chippewa to bring their families by late October from hundreds of miles away to Sandy Lake for the annual treaty payments. Watrous was in St. Louis at the time and didn’t make arrangements for provisions to be available once the numerous bands arrived. According to the book “Chippewa Treaty Rights” by Ronald N. Satz, the subagent also had recommended infantry personnel go to La Pointe on Madeline Island for the “general removal” of Lake Superior tribal members. Chief Buffalo and other tribal headmen said in a December 1850 letter sent to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington that they “feel ourselves aggrieved and wronged by the conduct of the U.S. Agent John I. Watrous and his advisors now among us. He has used great deception towards us in carrying out the wishes of our Great Father in respect to our removal.” Watrous and Ramsey in 1851 tried again to move the payments to Sandy Lake. But many tribal members refused. An 1851 article in the New York Times accused Watrous of an “iniquitous scheme” to remove the Chippewa people.

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor was U.S. president from 1849 to 1850 as a Whig Party member. Born in Virginia, Taylor was the last president to own slaves while in office. Taylor issued an executive order in 1850 for removal of Chippewa bands east of the Mississippi from their homes to “unceded lands” to the west. Taylor wasn’t a stranger to Minnesota. As Lt. Colonel Taylor, he commanded Fort Snelling in Minnesota in 1828 and 1829. Taylor died unexpectedly in office in July 1850 after developing a fever. Vice President Millard Fillmore took office and replaced all the cabinet members. President Fillmore in 1852 met with Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong and stopped any efforts to remove the bands.

Alexander Ramsey

Alexander Ramsey was the Territorial Governor of Minnesota from 1849 to 1853 as a Whig Party member. He was appointed to the position by President Zachary Taylor. A Minnesota State History Marker notes: “Ramsey and others claimed they were acting to ‘ensure the security and tranquility of white settlements.’ But their true motivation was economic.” Chippewa Chief Flat Mouth in 1850 said: “Tell him I blame him for the children we have lost, for the sickness we have suffered, and for the hunger we have endured. The fault rests on his shoulders.” For more on Chief Flat Mouth, click here. Ramsey also is remembered for this statement: “The Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of the state.”

‘When we left for home we saw the ground covered with the graves of our children and relatives’

Chief Buffalo. followed by more than two dozen other tribal leaders and members meeting at La Pointe, signed this letter to the president in November 1851.

“To the Hon. Luke Lea. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Washington, D.C.

Our Father: We send you our salutations and wish you to listen to our words. We the Chiefs and head men of the Chippeway Tribe of Indians, feel ourselves aggrieved and wronged by the conduct of the U.S. Agent John I. Watrous and his advisors now among us. He has used great deception towards us in carrying out the wishes of our Great Father in respect to our removal. We have ever been ready to listen to the words of our Great Father whenever he has spoken to us, and to accede to his wishes. But this time, in the matter of our removal, we are in the dark ... Now the man you have sent to be our agent has removed our payment to a distant place ... We wish to speak now of our payment at Sandy Lake, how we suffered and were deceived there by our Agent. This is what our Agent told us. "Come, my children, come to Sandy Lake and you shall have plenty to eat and be fat and I will make your payment quick." We went, but did not find him there ... Instead of having a good supply of provisions to eat, we had but little; and the pork & flour furnished us had been soaked in the water, and was so much damaged that we could not eat it. It was this that caused so much sickness among us. After being kept there two months waiting for our payment, the Agent at length arrived and paid us our goods, but our money we did not get at all. By this time the rivers had frozen and we had to throw away our canoes and go to our distant homes with our families on foot. As the Agent did not supply us with provisions we were obliged to sell our blankets and buy on credit with the traders, that our children might be kept from starving and we have something to eat during our journey home. When we left for home we saw the ground covered with the graves of our children and relatives. One hundred and seventy had died during the payment. Many, too, of our young men and women fell by the way, and when we had reached home and made a careful estimate of our loss of life, we found that two hundred and thirty more had died on their way home. This is what makes us so sad to think that the payment should be removed to that place ...”

Other quotes about the Sandy Lake Tragedy

The Rev. John H. Pitezel in his 1857 book “Lights and Shades of Missionary Life” wrote:

“Frequently, seven or eight died a day. So alarming was the mortality that the Indians complained that they could not bury their dead. Coffins could not be procured, and often the body of the deceased was wrapped up in a piece of bark and buried slightly underground. At times a hole was dug and several corpses together thrown in and covered up ... All over the cleared land graves were to be seen in every direction, for miles distant, from Sandy Lake; they were to be found in the woods.”

A missionary wife about a family going back to Leech Lake said:

“Three days’ march from Leech Lake, the two children were taken sick, the oldest a boy of twelve years old. The father was obliged to carry his sick son, and the mother the daughter, until the last night before they reached Leech Lake, when the boy died. The next morning they set off again, the father carrying the corpse of his son, and the mother a sick child. About noon the girl died, but they came on until they reached Leech Lake, bringing the dead bodies of their children on their backs.”

Here are the 12 modern-day tribal successors to the 19 bands at Sandy Lake in 1850:

Wisconsin: Bad River Band, Lac Courte Oreilles Band, Lac du Flambeau Band, Red Cliff Band, St. Croix Band and Sokaogon Band.

Minnesota: Fond du Lac Band, Grand Portage Band, Leech Lake Band and Mille Lacs Band.

Michigan: Keweenaw Bay Indian Community and Lac Vieux Desert Band.

This site is published by a member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. Click here for more information