Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong

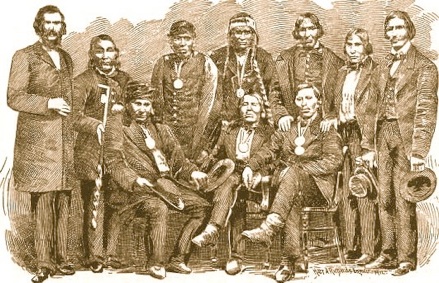

Armstrong and a delegation of Chippewa chiefs meet with Lincoln

President Lincoln’s Commissioner of Indian Affairs William Dole appointed Benjamin Armstrong as a special interpreter. Armstrong selected a delegation of nine Chippewa chiefs from Minnesota and Wisconsin to meet with President Lincoln in the early years of the Civil War. He wrote: “Agent Webb, myself and others had frequent talks over the general outlook for Indian troubles and it was finally decided to take a delegation on a trip through the states and to Washington, as such a trip would give the delegation a rare chance to see the white soldiers and to thus impress upon their minds the futility of any further recourse to arms on their part.” The delegation left Bayfield in early December 1861 and returned in mid-April 1862 1862.

Background on some of the chiefs

Ah-moose (Little Bee) from Lac Flambeau Reservation. Warren Whipple Warren’s “History of the Ojibway People” discusses the ancestry and status of Ah-moose, or Ah-mose and Ah-mous. Warren writes: “Waub-ish-gang-aug-e (White Crow), the son and successor of Keesh-ke-mun, fully sustained the influence of his deceased father over the inland bands, till his death in 1847. His son Ah-mous (the Little Bee), though lacking the firmness, energy, and noble appearance of his fathers, and though their formerly large concentrated bands are now split up by the policy of the traders and United States agents into numerous small factions headed by new-made upstart chiefs, yet virtually, in the estimation of his tribe, he holds the first rank over the Lac du Flambeau and Chippeway River division, and his right to a first rank in the councils of his peoples is unquestioned.”

Kish-ke-taw-ug (Cut Ear) from Bad River Reservation. Also known as Kis-ke-ta-wak and Giishkitawag (The Cut Ear) was a signer of the 1837, 1842 and 1854 treaties.

Ba-quas (He Sews) from Lac Courte O’Rielles Reservation. Also known as Bay-goosh.

Ah-do-ga-zik (Last Day) from Bad River Reservation. Also known as A-duh-wih-gee-zhig. The Wisconsin Archeologist in 1928 noted: “A-duh-wih-gee-zhig was a chief of the La Pointe band of Chippewa. His name signifies ‘on both sides of the sky or day.’ His father was Mih-zieh, meaning a ‘fish without scales.’ The chieftainship of A-duh-wih-gee-zhig was certified to by the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs on March 22, 1880.”

Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation. A New York Times article with the headline “The Red Men” on July 27, 1871 notes: “The Toronto Telegraph of the 24th ... contains an account of Little Pine, a Chippewa chief, from the shores of Lake Superior, and of the objects of a visit he is now making to that city in company with a missionary. R. E. F. Wilson.” The Wisconsin Archeologist in 1928 noted that Little Pine was “a mixed-blood from Bayfield.”

Na-gon-ab (He Sits Ahead) from Fond du Lac Reservation. Also known as Na-ga-nub (The Foremost Sitter or Sitting Ahead). Na-gon-ab’s statements in Benjamin Armstrong’s memoirs have quoted by legal and other academics regarding how tribal members viewed and understood treaty negotiations and promises. Na-gon-ab said: “We depend upon our memory. We have nothing else to look to. We talk often together and keep your words clear in our minds. When you talk we all listen, then we talk it over many times. In this way it is always fresh with us. This is the way we must keep our record. In 1837 we were asked to sell our timber and minerals. In 1842 we were asked to do the same. Our white brothers told us the great father did not want the land. We should keep it to hunt on. Bye and bye we were told to go away; to go and leave our friends that were buried yesterday. Then we asked each other what it meant. Does the great father tell the truth? Does he keep his promises? We cannot help ourselves! We try to do as we agree in treaty. We ask you what this means? You do not tell from memory! You go to your black marks and say this is what those men put down; this is what they said when they made the treaty. The men we talk with don't come back; they do not come and you tell us they did not tell us so! We ask you where they are? You say you do not know or that they are dead and gone.”

A side note on Chief Na-ga-nub and Armstrong: Attorney and politician William Freeman Vilas in August 1873 left Bayfield on the steamer Cuyahoga to Duluth. On board “was Ojibwe Chief Nagonab, with interpreter Benjamin Armstrong, who invited the passengers to a talk in the cabin. The captain undoubtedly arranged for the talk as entertainment for the passengers, but Nagonab took the opportunity to speak not only about his experiences with the white people but also his grievances. The talk was lengthy and Vilas took detailed notes.” This is according to the 2008 publication, “People and Places: A Human History of the Apostle Islands” by Jane C. Busch. Villas later served in the U.S. Senate from Wisconsin, from 1891 to 1897.

Chief Na-gon-ab died at Fond du Lac in 1894, at an age of nearly 100.

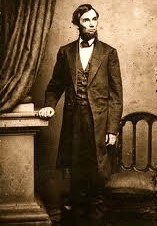

‘My children, when you are ready, go home and tell your people what the great father said to you; tell them that as soon as the trouble with my white children is settled I will call you back and see that you are paid every dollar that is your due’

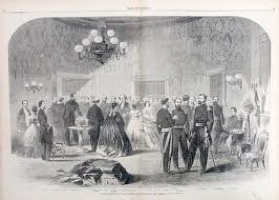

Passage from “Early Life Among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong” on meeting with President Abraham Lincoln in Washington:

“I was appointed by Commissioner Dole, who had charge of Indian affairs under President Lincoln, to act as special interpreter for Gen. L. E. Webb, the Indian Agent at Bayfield, Wisconsin, and Clark W. Thompson, superintendent of Indian affairs in the northwest, who was located in St. Paul, Minnesota. I accepted the appointment and performed the duties of interpreter until the fall of 1864. I moved my family from Oak Island to Bayfield ... A scare was started throughout this country to the effect that an uprising of the Indians was quite likely, which resulted in bringing three companies of soldiers to Bayfield and the same number to Superior ... Agent Webb, myself and others had frequent talks over the general outlook for Indian troubles and it was finally decided to take a delegation on a trip through the states and to Washington, as such a trip would give the delegation a rare chance to see the white soldiers and to thus impress upon their minds the futility of any further recourse to arms on their part ... I selected a party of nine chiefs from the different reservations ... We set out about December 1st, 1861, going from Bayfield, Wis., to St. Paul, Minn., by trail, and from St. Paul to La Crosse, Wis., by stage, and by rail the balance of the way to Washington. Great crowds of soldiers were seen at all points east of La Crosse, besides train loads of them all along the whole route, besides train loads of them all along the whole route. Reaching Washington ... They witnessed a number of drills and parades, which had a salutary effect upon their ideas of comparative strength with their white brothers. Being continually with them I frequently heard remarks passing between them that showed their thoughts respecting the strength of the white race. ‘There is no end to them,’ said one. ‘They are like the trees in our forest’ said another ... I was furnished with a pass to take them to the navy yard and to visit the barracks of the Army of the Potomac, at which place one of them remarked that the great father had more soldiers in Washington alone than there were Indians in the northwest, including Chippewas and Sioux, and that his ammunition and provisions never gave out. We remained in the city about forty days and had interviews with the Indian Commissioner and the President ... The President made a short speech to the Indians at one of these interviews, at which he said: ‘My children, when you are ready, go home and tell your people what the great father said to you; tell them that as soon as the trouble with my white children is settled I will call you back and see that you are paid every dollar that is your due, provided I am here to attend to it, and in case I am not here to attend to it myself, I shall instruct my successor to fulfill the promises I make you here today.' After visiting all places of interest in Washington, and about a week after the last interview with the President, we set out on our home journey.”

Armstrong later wrote about Lincoln’s promises of payments to the tribe:

“There is now large sums of money still due the Indians under the treaties of 1837, 1842 and 1854. As I had occasion and did look over the records in Washington in 1862, I am justified in making this statement. The Indians have very often since that time inquired of me what I had found, and feeling that I ought not to keep it secret from them by reason of the part I took in the treaty of 1854, I always told them as near as possible what I had found the records to contain. These talks and inquiries continue to the present time, and I am asked why it is that the great father's words are not made true. The older Indians have not forgotten what President Lincoln told the delegation in 1862, and the younger ones know it also, which was to ‘return home and tell your people as soon as the trouble with my white children has been settled I will attend to you and see that every dollar that is your due is paid.’ I have made several attempts myself to bring this settlement about but have never been able to do so.”

At the top is an illustration in Benjamin Armstrong’s 1892 memoirs with the caption, “The Delegation Before President Lincoln, 1862.” Some appear to be wearing Presidential Indian Peace Medals. Armstrong lists the chiefs as: Ah-moose (Little Bee) from Lac Flambeau Reservation, Kish-ke-taw-ug (Cut Ear) from Bad River Reservation, Ba-quas (He Sews) from Lac Courte O’Rielles Reservation, Ah-do-ga-zik (Last Day) from Bad River Reservation, O-be-quot (Firm) from Fond du Lac Reservation, Sing-quak-onse (Little Pine) from La Pointe Reservation, Ja-ge-gwa-yo (Can’t Tell) from La Pointe Reservation, Na-gon-ab (He Sits Ahead) from Fond du Lac Reservation, and O-ma-shin-a-way (Messenger) from Bad River Reservation. (Please note that a similar looking picture on the Internet has been used to identify a group of different tribal members.)

This site is published by a member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. Click here for more information