Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong

The 1852 journey to Washington, D.C.

Government agents in Washington and the frontier in the late 1840s had started the efforts to remove the Lake Superior Chippewa people from their homeland. Officials changed the location of the treaty payments to a place in Minnesota that would require a long trek by canoe and on foot. Their hope was that the tribal members would not return home. Known as the Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850, the result was the death of hundreds of people because of delayed payments, tainted food, disease and the onset of winter. Because of the Sandy Lake Tragedy and other events, tribal leaders decided to take action before an uprising resulted in possible bloodshed. Chief Buffalo, his under chief O-sha-ga, four braves and Benjamin Armstrong set off before noon on April 5, 1852 in a 24-foot birch bark canoe from Lake Superior’s Madeline Island. It was the start of their “illegal” journey to Washington to keep the peace back home and halt the removal efforts.

The book “Ojibwe Journeys” published the the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission notes: “The 93-year-old Chief Buffalo making the journey to Washington, D.C., paddling a quarter of the way in a canoe to defend tribal treaty rights, speaks volumes, and so eloquently, of the sacrifice, pain and determination many have gone through to defend our legal and human rights all the while envisioning a better world for our children.”

Benjamin Armstrong wrote about the journey: “We made the mouth of the Montreal River, the dividing line between Wisconsin and Michigan, the first night, where we went ashore and camped, without covering, except our blankets. We carried a small amount of provisions with us, some crackers, sugar and coffee, and depended on game and fish for meat.” But storms, a lack of money and other trouble later came. Border agents tried to turn the men back for making a trip unapproved by the federal government. “We do not think you will ever reach Washington,” one agent told them. The group later traveled by boat and train, seeing a railroad car for the first time in their lives.

They arrived in Washington on June 22, after traveling for more than 10 weeks, including a stop in New York City. Once in Washington, they ran into more resistance from government officials. They were told to go home, despite explaining what might result if their journey was a failure. Below, read “A Meeting with the President” on how a chance encounter with a New York congressman resulted in smoking a peace pipe with President Millard Fillmore, halting attempts to remove the Lake Superior Chippewa, and setting the stage for the 1854 treaty.

‘I had just and only one ten-cent silver piece of money left’

Passage from “Early Life Among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong” on the stop in New York City on the way to Washington:

“We landed in New York City without mishap and I had just and only one ten-cent silver piece of money left. ... I told the landlord of my financial embarrassment and that we must stay over night at any rate and in some way the necessary money to pay the bill should be raised. I found this landlord a prince of good fellows and was always glad that I met him. I told him of the letters I had to parties in the city and should I fail in getting assistance from them I should exhibit my fellows and in this way raise the necessary funds to pay my bill and carry us to our destination. He thought the scheme a good one, and that himself and me were just the ones to carry it out.”

”You can imagine my own feelings on this occasion, for, like the Indians, I had been brought up in a wilderness, entirely unaccustomed to the society of refined and educated people ... The hostess, addressing me, said it was the wish of those present that in eating their supper the Indians would conform strictly to their home habits, to insure which, as supper was then being put in readiness for them, I told the Indians that when the meal had been set before them on the table, they should rise up and pushing their chairs back, seat themselves upon the floor, taking with them only the plate of food and the knife. They did this nicely, and the meal was taken in true Indian style, much to the gratification of the assemblage. When the meal was completed each man placed his knife and plate back upon the table, and, moving back towards the walls of the room, seated himself upon the floor in true Indian fashion.”

A meeting with the president

Once in Washington, Benjamin Armstrong’s first attempts to meet with federal officials were fruitless. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs told him: “I want you to take your Indians away on the next train west, as they have come here without permission and I do not want to see you or hear of your Indians again." The office of the Secretary of the Interior told him: "Did you have permission to come, and why did you not go to your agent in the west for permission? I can do nothing for you. You must go to the Indian Commissioner." Armstrong returned to the hotel to find Chief Buffalo surrounded by a crowd. Armstrong explained to the hotel steward the situation. The steward replied: "Why don't you take him into the dining room with you? Certainly such a distinguished man as he, the head of the Chippewa people, should have at least that privilege." Armstrong did so. It was in this dining room that a member of Congress and members of President Fillmore’s cabinet stopped at the pair’s table. From that, a meeting with the president was arranged. Here’s how Armstrong describes the meeting:

“The pipe, a new one brought for the purpose, was filled and lighted by Buffalo and passed to the President who took two or three draughts from it, and smiling said, ‘Who is the next?’ at which Buffalo pointed out Senator Briggs and desired he should be the next. The Senator smoked and the pipe was passed to me and others, including the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Secretary of the Interior and several others whose names I did not learn or cannot recall. From them to Buffalo, then to O-sha-ga, and from him to four braves in turn, which completed that part of the ceremony. The pipe was then taken from the stem and handed to me for safe keeping, never to be used again on any occasion. I have the pipe still in my possession and the instructions of Buffalo have been faithfully kept. The old chief now rose from his seat, the balance following his example and marched in single file to the President and the general hand-shaking that was began with the President was continued by the Indians with all those present.

This over Buffalo said his under chief, O-sha-ga, would state the object of our visit and he hoped the great father would give them some guarantee that would quiet the excitement in his country and keep his young men peaceable. After I had this speech thoroughly interpreted, O-sha-ga began and spoke for nearly an hour. He began with the treaty of 1837 and showed plainly what the Indians understood the treaty to be. He next took up the treaty of 1842 and said he did not understand that in either treaty they had ceded away the land and he further understood in both cases that the Indians were never to be asked to remove from the lands included in those treaties, provided they were peaceable and behaved themselves and this they had done. When the order to move came Chief Buffalo sent runners out in all directions to seek for reasons and causes for the order, but all those men returned without finding a single reason among all the Superior and Mississippi Indians why the great father had become displeased.

When O-sha-ga had finished his speech I presented the petition I had brought and quickly discovered that the President did recognize some names upon it, which gave me new courage. When the reading and examination of it had been concluded the meeting was adjourned, the President directing the Indian Commissioner to say to the landlord at the hotel that our hotel bills would be paid by the government. He also directed that we were to have the freedom of the city for a week.

The second day following this Senator Briggs informed me that the President desired another interview that day, in accordance with which request we went to the White House soon after dinner and meeting the President, he told the delegation in a brief speech that he would countermand the removal order and that the annuity payments would be made at La Pointe as before and hoped that in the future there would be no further cause for complaint. At this he handed to Buffalo a written instrument which he said would explain to his people when interpreted the promises he had made as to the removal order and payment of annuities at La Pointe and hoped when he had returned home he would call his chiefs together and have all the statements therein contained explained fully to them as the words of their great father at Washington.”

Note: O-Sha-ga also is referred as O-Sho-ga in Armstrong’s book.

Meetings with two other U.S. presidents

In contrast to the 1852 journey, Chief Buffalo traveled to Washington again in 1855 as an invited guest to meet with President Franklin Pierce. You can find out more about that meeting in the “U.S. Capitol busts” section of this Web site.

After Chief Buffalo’s death, Benjamin Armstrong was appointed by President Lincoln’s Commissioner of Indian Affairs as a special interpreter. Armstrong selected nine Minnesota and Wisconsin chiefs for a delegation to confer with President Lincoln. You can find out more about that trip in the “Meeting with Lincoln” section of this Web site.

Federal officials they met with in Washington

Millard Fillmore, 13th president, from 1850 to 1853

Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart, Interior secretary from 1850 to 1853

New York Congressman George Briggs (Note: The passage to the right mistakenly refers to Briggs as a senator.)

Not pictured: Luke Lea, Commissioner of Indian Affairs from 1850 to 1853

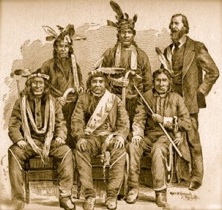

Clockwise from the top: A scene from Armstrong’s book of the conditions the delegation encountered on the trip to Washington; an illustration from the book of part of the delegation in June 1852 upon their arrival; and a view from Capitol Hill in 1852.

This site is published by a member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. Click here for more information